* The timeline is part of the digital exhibition 'Changing Perspectives: a garden through time' http://agardenthroughtime.com/timeline/

With especial thanks to Bernie Wallman, President of the Cambridge Granta South Road Homing Society]

|

|

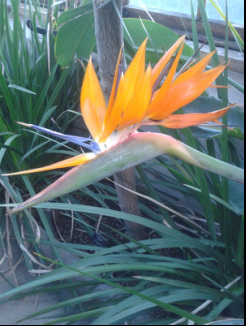

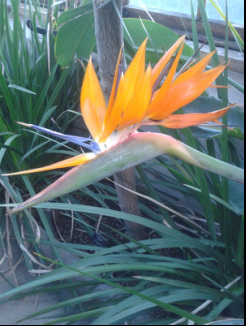

February sees me still scraping away at the surface of things, trying to arrive at a clearer picture of the garden and what it all means. Part of this process for a writer of fiction naturally involves allowing the imagination space to wander. For some time I’ve been preoccupied with the eastern end of the garden where the allotments used to be. Sitting on one of the commemorative benches, watching, listening, thinking, I found myself inhabiting the skin of a widower looking back over his married life. I imagined an allotment for him, complete with pigeon loft. Historically, I think this is unlikely. Still, it has a kind of truth in the world of the story, and comes to represent both happiness and loss. And so, although this part of the tale is pure invention, I want to make sure that the details I’ve included ring true. Which explains how I end up spending an absorbing afternoon in the company of Shelford pigeon fancier Bernie Wallman. I learn the history of Bernie’s own fascination with breeding and racing pigeons and some of their remarkable feats of distance and stamina. The bird in the picture is a diploma-winner with 13 cross-channel races to his name. I meet the birds in his three lofts; I even get one of the older birds to take nuts from my hand. In the event, what I had imagined proved close enough and I didn’t change what I’d written, but I wouldn’t have missed my outing for the world.  Journeys of a different kind have kept me busy too. I’ve been reading about plant hunters, those intrepid explorers who braved danger and disease, intense cold or heat (sometimes both) and exhaustion to collect, between them, tens of thousands of new species from across the world. Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, arguably the ‘most important botanist of the nineteenth century’, began his collecting by joining Captain James Clark Ross’s 4-year Antarctic voyage as assistant ship’s doctor and botanist on board the Erebus – the same ship which, refitted with a steam engine, set out a couple of years later for the Arctic under the command of Sir John Franklin and became icebound, resulting in the loss of the whole expedition, some 130 men. The story has reverberated in popular song (‘Lady Franklin’s Lament’) and story. Hooker, though, survived the ship’s previous voyage and went on to travel in Sikkim, amassing a huge collection of rhododendrons and devoting himself to a lifelong study of plants. I loved imagining him setting out morning after morning, walking, battling altitude sickness, collecting specimens and then writing up his journal, drawing (beautifully) and cataloguing his findings by the light of a lantern, enjoying ‘the small luxury of his evening cigar’. Seventy years earlier Francis Masson, went from under-gardener to become Kew’s first official plant hunter, accompanying Captain Cook’s second circumnavigation. An extended exploration of South Africa’s Cape produced a collection of 400 new species including the extraordinary bird of paradise Strelitzia reginae, currently flowering in the glasshouse corridor here. Masson sadly died in Canada on his last journey.  My own exploration of the glasshouses has been slow to start and I’m not sure why. At any rate, I mean to make up for lost time and start methodically at the eastern end with ‘Arid Lands’ . Or perhaps I’ve chosen this on the basis of getting the worst over first: the cactus is not my favourite life form. Actually it’s a delightful spot to while away an hour or two on one of these nippy winter days of full sun and clear skies. I sit on the bench at the far end, my back to the bee beds and the misted panes on which visiting school children, I’m guessing, have left their mark: ‘Hoi Daniel Dunlavey’, ‘I EAT POO’ and the inevitable ‘lol’. The actual plants aside, the forms are lovely, the arrangement of tall thrusting columns and spreading discs, spikes and spines, menacing globes of pin-cushion sharpness and clean rock surface… I take a few photos and then sit back to let the summery drone of wood pigeons wash over me…  And that’s when it happens: I’m looking up at the roof and I see, first, the looped metal dividers in the sloping panes of the roof and how they suggest that the panes themselves are curved rather than flat. Next I see a metal hinge, a series of hinges, an upright strut, a whole skeleton of iron which supports the elaborate confection of wood (teak, I’m sure I read somewhere) and glass. It’s a little like falling in love, that unexpected toppling sensation where excitement tips into giddiness with the discovery: because here’s another story, one of those stories-beneath-the-story ones, and it feels like home from home for a railwayman’s daughter. Without this engineered backbone, the glasshouse itself would crash, and where would cactus and succulent be then? I’m reminded of looking upwards in Carlisle station recently, or at the soaring flights of roof in the new St Pancras or King’s Cross. And all the time I’m wondering, where did all this come from? Who made it?  Well there’s a clue: the name printed on part of the window mechanism is clear enough, and a little poking about on the web produces very satisfying results. William Richardson was born at Langbaurgh Hall in Great Ayton, North Yorkshire into a Quaker family and in 1850, aged 14, moved to the Quaker town of Darlington, already home to the world’s first passenger railway the ‘Quaker Line’. There he teamed up with John Ross and the two, probably apprenticed to Joseph Sparkes, began to make their names as architects. The Great Exhibition of 1851 strengthened the new vogue for glass houses and Richardson’s signature on designs from this year shows that at the age of 15 the young entrepreneur was already going places. Ross & Richardson took over the business when Sparkes died then, after five years designing for the top of the market, Richardson took up joinery, dabbled in furniture and began establishing a name for himself in greenhouses. Within twelve years he had built the North of England Horticultural Works in Darlington. By his mid-fifties he was building hothouses across Europe – including the first pine glasshouses at Cambridge’s botanic garden in 1888? – and heating them with ‘an apparatus called a radiator’, winning contracts for heating hospitals, schools and cathedrals. He died in 1921, the year after my dad was born, at the age of 85, so didn’t live to see the 1930s rebuilding of the Cambridge glasshouses, credited jointly to W. Richardson & the Edinburgh foundry Mackenzie & Moncur.  I’m already imagining the young William with his pencil, sitting him alongside Hooker and his cigar, when a little further reading pulls me up short: the records of the syndicate of the botanic garden in Cambridge attribute the building of the first pine glasshouses in 1888 to the firm Boyd of Paisley. More digging: James Boyd & Sons originated with glazier James Boyd who opened a shop in Paisley High Street in 1826. Apparently the abolition of tax on glass in 1848 encouraged the building of conservatories and glass houses. Since Boyd was also a joiner he was able to exploit the new market & by 1851 he was advertising as a ‘hot-house builder’. As well as work in Scotland, the firm built conservatories and palm houses in Ireland and South Africa – no mention of Cambridge, although the Cambridge botanic garden's timeline* credits the firm with rebuilding James Stratton’s 1855 glasshouse range in ‘white-painted pinewood’. By the 1920s the Boyd firm had split into two, boilermakers & engineers, & an insurance company; hothouses had become a thing of the past.  The timeline is an invaluable resource which constructs a clear sequential narrative of the garden’s own story. In a way it would have been easier had I started there. But the twists and turns, false trails and blind alleys, are the stuff of which stories are made. I’ve recently met up with someone who went to the same school as me in London years ago, and we had a good laugh remembering the vagaries of the system and some of its more idiosyncratic members. I can recall a rather terrifying history teacher, and those were certainly the days when history was taught (by the teacher) and learnt (by the pupil) and no questions asked. Now, we are encouraged to have a critical view of our sources, of the context in which the knowledge is gained. I’m thinking of those early explorers carefully recording what they found, of the gardeners before and since who have logged their plantings and prunings, the school kids who leave their signature on the glass, and the writer who picks up a broken bit of china in the newly turned earth, turns it over in her fingers, brushing off the soil, and imagines the rest of the cup and the hands that held it to the lips… [I read The Plant Hunters by Toby Musgrave, Chris Gardner & Will Musgrave

* The timeline is part of the digital exhibition 'Changing Perspectives: a garden through time' http://agardenthroughtime.com/timeline/ With especial thanks to Bernie Wallman, President of the Cambridge Granta South Road Homing Society]

1 Comment

Janet Green

6/2/2014 10:18:24 am

I love the way your brain shoots off and you start researching !! It takes me by surprise every time!!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

At HomeAs Writer in Residence, thoughts from the garden Archives

October 2020

Categories |