MARIA

A new chapter: after the fourth rewrite, a new title.

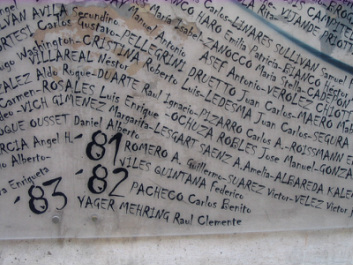

Thumbprint: Cordoba's Disappeared

(detail) Halfacree 2010

MARIA is a literary novel which deals with a political and historical topic on a personal level. Set in Buenos Aires and Córdoba, Argentina’s second city, the narrative moves between the mid-1970s and the present day. The novel explores the story of The Disappeared, those whose lives were erased by the forces of repression in the name of national security and order. It focuses on the impact of the disappearances on the individual and examines themes of our relationship with the past, loss and recovery, and the search for truth. Books that I had in mind while writing this novel were A.L. Kennedy’s Day and Margaret Atwood’s A Handmaid’s Tale.

The novel begins with a prologue, set in 1976: the voice of Maria as she prepares for the birth of her daughter, Elena. The main body of the narrative then shifts to the present day. Nadia Perotti has left her London home to teach in Buenos Aires, where she meets an older man, Álvaro Becerra. Flattered by his attention and charmed by his generosity, she finds herself becoming close to him although she knows little about his past. However, when she becomes involved with Milo Garcia and his project at one of the city's slums, she begins to discover the history of the disappearances and also learns that Álvaro is not who he seems. Álvaro meanwhile is forced to confront the horror of his country’s heritage, as well as the extent of his own guilt. The process of his internal disintegration is shared by the reader and is also mirrored in the external conflict as the net closes round him. The stories of Maria and Elena emerge through the narrative. The novel offers the reader a sense of the indefatigable courage and endurance of the human heart, as well as its capacity for evil.

Extract

PROLOGUE: CÓRDOBA 1976

Almost time. Months, days of waiting, my waist thickening, breasts swollen, tender to the touch. As the pain eases, I put my hand on my belly, stretched tight, a defence against danger. I feel you shift in the warmth inside me. My fingers find a hard shape, your elbow or a knee perhaps, that thrusts as you nuzzle my palm in greeting. How shall I reply?

I could say, it is cooler out here, and almost silent. I try telegraphing the message with a double squeeze of index finger and thumb. The nights can be cold, but sometimes there is sunshine. When they brought us food this morning, I could see my ankles. A thin strip of sunlight lay across them like sticking plaster, a promise that wounds can be healed, that there is a world outside this room. I looked down the row of beds. I saw the air thick with dust motes that hung suspended over the thin blankets and the women beneath. There was dust on the floor, too; beneath the bed next to me, a small drift had collected where the lino was cracked. I stored these details, the sun, the dust. Now, in the dark, an experiment: if I remember the dust, magnify each particle in my mind, and count, perhaps the pain will be less.

The beds are so close together that it is easy for the woman next to me to reach across and touch my hand. I do not know who she is. I think they brought her in this morning. There was no sound, and then I began to hear the papery flutter of her breath. I imagine she has stayed curled small into the wall, until now. Now we lie joined like lovers on the grass on a spring night, looking up at the black sky, without speaking. There is nothing for us to say. Our separate lives have met in this point, converged in a single destiny. Like lovers, we know nothing about each other, and at the same time everything we need to know.

The next pain hits like a wall of water, and I cling to her hand as she folds her other on top of mine. I breathe, and breathe, and count the breaths, winding backwards for each year, until I am seven again, standing by the old car that has brought us out of the city to the edge of the mountains. We have left the smog behind, and there are streaks of snow above us, and sky so blue I have to shout, and our father is shouting too, ‘Breathe, Maria! Feel how clean the air is!’ I breathe. We scramble down towards the river, the three of us and the three cousins, and we run across the wooden bridge, backwards and forwards, and there is cake and fruit, a glass of wine for the grown-ups, and then horse-riding for everybody. By the time we are ready to leave, darkness is collecting behind the nearest peak. I am squashed in the back as usual, held firm between the two bigger boys. I smell sugar and sweat and the leather of the car seats, and I taste the lungful of special mountain air. I press my lips together firmly: I think I can keep it always.

I want to tell you about always. I want to promise you that the mountain air is still clear, still free, that you will always be warm, safe inside. But as the last pain subsides, the next is already building. I imagine the sound it will make as it approaches, a low rumble, distant gunfire or the tracks of tanks over uneven ground. I think I am ready, yet at the same time I want to fight it, lock the muscles that must thrust you into this changed world. No chance: you shunt, impatient to be here, and I’m pushing and yelling.

I hear a rattle and a thud, a scraping sound that I think is a door opening. For a second, I think, this is help, a nurse, something to numb the hurt, to ease your journey; then I remember. I try to measure the progress of the voices and the footsteps in the darkness and I hear my voice shrill with panic until I realise they have stopped. I think they have stopped at Ana’s bed. The screams are louder but they are no longer mine. Instead, rage flares behind my eyes and I want to rip away the fabric that hides what they are doing. Then pity as the tears start. A hiatus in the pain and, to my shame, relief that it isn’t my turn, yet.

If Luis were here, I would hide my relief. He would take my hand and we would go to Ana’s bed, feeling our way in the dark, and stand strong in front of her, so that they would have to get past us first. Or we would whisper in the night, not of moonlight and kisses, but of ways to stop them, fighting talk. Then, his hand on my belly, he would wait for a kick or a turn of your shoulder, his lips moving over my face. His huge love would wrap around us, around this moment, soft as wool, hard as granite, and around Ana, and around the woman next to me, and the others. He would remind me that this is not our story alone. Mi casa es su casa, my grandmother used to say to visitors. My house is your house, my fate your fate.

I want to tell you where he is, that he is safe, perhaps in the next room, or just a few streets away. I want to tell you that your father is thinking of us, that his love is tough and enduring, that he will be here; that he will hold you in arms that are whole, or so that the marks are hidden. I want to tell you that they didn’t hurt him, or that the hands that beat him did so gently, or left their business half-finished; that at least he is alive. They must keep him alive: they need to find out what he knows. They will have the articles he wrote on the table in a small room; they will read them back to him, over and over, asking about names, what he saw, when it happened. But he won’t tell them. And so it will begin again. I don’t want to tell you this, but it is his story; it is our story too.

I try to hold on to the thought of Luis as the pain bites down on my body. His narrow forehead. Roughness of his chin. My finger on his lip. But even the spinning madness of what is happening to us, around us, is slammed to a halt and swallowed by this huge mouth. I’m inside. Dark. Wet. I push. I feel for his hands but they are nowhere and I shout out his name twice. The clatter of feet and more feet running and I shout again and I know now what I have known all along, that there is nothing I can do to keep you safe. Pushing. I have to shout out what I don’t want you to know, in case there is someone out there to hear. My voice lurches into a crazed litany. I call his name again, Luis, and your name that doesn’t even have a word yet, and Ana’s name. There is movement all around me, the screech of metal across the floor as the space shrinks. A sudden gust of garlic and sweat and the touch of something cool across my mouth and I knock it away. A thump to the side of my head that makes me gasp. A male voice; an obscenity; shrieks tear the air; a blur of fingers and the stink of disinfectant over the dirt and this grinding terrible pain, and you. You have had enough of waiting. You are coming, forcing yourself out into the noise. I rip the blindfold from my face. A burst of light, a clutter of sound welcomes you: laughter. In my head, echoes: a fist hammers on the door in the night; a scream is muffled by a hood; and voices, quietly at first, speaking their names, Alejandro, Alfredo, then louder, a chorus, Asuncion, Carla, Claudia. The room fills with the voices of the faceless. You add the first cry of a baby and your name, Elena. I hold you. I’m soaking, exhausted, but nothing matters except you, this moment, the smear of black hair, your miniature hands.

Then you're gone.

The writer wishes to acknowledge the kind assistance of Arts Council England