WRITING THE GARDEN

Sunday 10 December 2023

Hard to believe that it's more than 10 years since I took up the pen one May morning as writer in residence at Cambridge University Botanic Garden and made the first jottings recording my impressions. The 'journal' grew into a short story collection, one story for every month of the year, inspired by a particular feature of the garden and each introduced by a 'vignette' - although some of these introductions, as in the case of GLASSHOUSES below, sprawled into fully-fledged vignes...

Meanwhile I'm delighted that local artist and friend Carole Ellison has agreed to illustrate the collection and has produced some wonderfully original and striking pictures to accompany the stories. Now all we have to do is find a publisher!

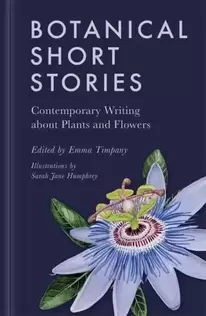

- for the collection as a whole, that is: I'm very pleased that 'Mercy', the story for the month of March, will be included in an anthology Botanical Short Stories, edited by Emma Timpany, to be published by The History Press in April 2024, and available to pre-order now:

https://blackwells.co.uk/bookshop/product/Botanical-Short-Stories-by-Emma-Timpany-editor/9781803993096

Meanwhile I'm delighted that local artist and friend Carole Ellison has agreed to illustrate the collection and has produced some wonderfully original and striking pictures to accompany the stories. Now all we have to do is find a publisher!

- for the collection as a whole, that is: I'm very pleased that 'Mercy', the story for the month of March, will be included in an anthology Botanical Short Stories, edited by Emma Timpany, to be published by The History Press in April 2024, and available to pre-order now:

https://blackwells.co.uk/bookshop/product/Botanical-Short-Stories-by-Emma-Timpany-editor/9781803993096

DECEMBER: GLASSHOUSES

A perfect spot for a winter’s day. The early mist has cleared. Warmth and sunlight gather and linger within these glass walls. The glasshouse range begins, at the eastern end, in ‘Arid Lands’. Sit on the bench, your back to the Bee Beds and the misted panes where visiting school-children have left their mark. Look along the dry river bed created by the paving at rock and pale earth and imagine yourself on the other side of the world. The plants here have developed to survive on little water and extreme temperatures, often very hot during the day but freezing at night, and operate on a grand scale. The African aloes on one side and the South American agaves in the opposite bed spread horizontally into fleshy whorls which store water and direct rainfall to the roots, whilst their flowers shoot up, the orange-pink cones of Aloe arborescens ablaze in keeping with its common name ‘torch aloe’. The cacti swell into spheres or soar vertically, knuckled fingers thrusting upwards. Some are eight or ten feet high. Shape and form predominate, the stretch and reach of the plants echoed in the architecture of the building itself. It’s no surprise that these plants are favourites of illustrators: look at Marianne North’s lovely ‘Cactus-like plant growing close to the sea in Tenerife’ in her gallery at Kew, or Derek Wood’s colour pastel of Cereus validus on the Botanic Garden’s website. Their extraordinary forms would be tempting to touch were it not for the armour of thorns and spines which deter grazers as well as human hands. The hair-like spines or glochids on the surface of the prickly pear Opuntia easily detach and lodge in the skin, and can be difficult to remove. Some species of prickly pear are edible, though: in Mexico nopales – from the Nahuatl word for paddle – are delicious in tacos, and the pulp and fruit have been widely used in folk medicine there. The Opuntia microdasys in Arid Lands, familiarly known as bunny-ears or polka-dot cactus, has bright yellow flowers...

...and here is the opening of its accompanying story:

LIFE SENTENCE

Another grey day, cloud draped over the street like a dirty old blanket. Somewhere beyond the glass, a bird is singing, the same notes over and over – why bother? He chucks the rest of the toast in the bin and slams the door behind him.

After last night’s storms there’s no wind to speak of, only the tops of the trees fidgeting as he clears the houses and turns onto the main road. Across the footbridge, the boards slippery with the wet, the river almost over the bank. Ducks and swans huddle on the steps. On the commons, mist hangs a metre above the mud. The air is damp, too, though it feels sharp enough to graze the skin on his cheekbones. His knuckles are red raw where they grip the handlebars.

He freewheels to the end of the path, then digs in half-standing, pushes his feet into the pedals, past a man tugging at what looks like a rat on a lead, leans into the bend by The Maypole, through the bollards and across onto the pavement. A straggle of Chinese at the bus stop step out of his way, but the old feller at the end of the queue is not so quick and the back wheel catches on his coat tails as he passes. Will grins as the guy’s shouts follow him over the junction and down the cobbles towards King’s. The good mood doesn’t last. Even the high-speed slalom-and-scatter through drifts of tourists and rich kids fails to lift his spirits, and he locks the bike to the railings with a heavy heart.

Day four of fourteen: there are worse places, though he’s hard pushed to think of any right now. A litter of leaves, some as big as dinner plates, are scattered across the grass by the gate – brought down by the gales in the night, since he’d cleared the lawns as it grew dark yesterday. And his first job of the day again this morning, no doubt. So what was the point exactly? He grubs around in the blur of schooldays for the name of the character, some Greek bloke, who was made to carry out the same stupid task every day – push a rock up a mountain, or something? – but it’s gone, along with the reason for the punishment. He shrugs, hitches the backpack higher on his shoulders and, head down, sets off round the perimeter. Even if he’s incapable of arriving late, he’s not going to give them the satisfaction of reporting early for duty, persuading them that he’s on the road to reform...

LIFE SENTENCE

Another grey day, cloud draped over the street like a dirty old blanket. Somewhere beyond the glass, a bird is singing, the same notes over and over – why bother? He chucks the rest of the toast in the bin and slams the door behind him.

After last night’s storms there’s no wind to speak of, only the tops of the trees fidgeting as he clears the houses and turns onto the main road. Across the footbridge, the boards slippery with the wet, the river almost over the bank. Ducks and swans huddle on the steps. On the commons, mist hangs a metre above the mud. The air is damp, too, though it feels sharp enough to graze the skin on his cheekbones. His knuckles are red raw where they grip the handlebars.

He freewheels to the end of the path, then digs in half-standing, pushes his feet into the pedals, past a man tugging at what looks like a rat on a lead, leans into the bend by The Maypole, through the bollards and across onto the pavement. A straggle of Chinese at the bus stop step out of his way, but the old feller at the end of the queue is not so quick and the back wheel catches on his coat tails as he passes. Will grins as the guy’s shouts follow him over the junction and down the cobbles towards King’s. The good mood doesn’t last. Even the high-speed slalom-and-scatter through drifts of tourists and rich kids fails to lift his spirits, and he locks the bike to the railings with a heavy heart.

Day four of fourteen: there are worse places, though he’s hard pushed to think of any right now. A litter of leaves, some as big as dinner plates, are scattered across the grass by the gate – brought down by the gales in the night, since he’d cleared the lawns as it grew dark yesterday. And his first job of the day again this morning, no doubt. So what was the point exactly? He grubs around in the blur of schooldays for the name of the character, some Greek bloke, who was made to carry out the same stupid task every day – push a rock up a mountain, or something? – but it’s gone, along with the reason for the punishment. He shrugs, hitches the backpack higher on his shoulders and, head down, sets off round the perimeter. Even if he’s incapable of arriving late, he’s not going to give them the satisfaction of reporting early for duty, persuading them that he’s on the road to reform...