Other reverberations from the weekend: I was mistaken for Madeleine Bunting. Two women stopped me for a photograph of my ‘amazing’ hair. I was reminded, courtesy of Rose Tremain, of the horror that the idea of exile can mean, and that the past is not simply past but lives on with us – to ‘entwine’ us was Paul Kingsnorth’s phrase I think. I was reminded, too, that we must write without fear – or was it to feel the fear and do it anyway? Meanwhile the sun is not far away and the avenue of bird cherry is prettily and fragrantly in flower across Jesus Green. So thank you Cambridge – on balance, it’s good to be here.

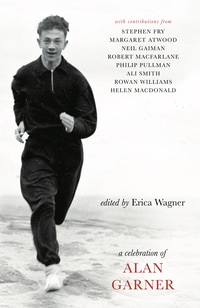

First Light, edited by Erica Wagner, was published by Unbound in 2016.

Ali's 3 debut writers this year were Luke Kennard for The Transition, Sally Rooney for Conversations with Friends and Eley Williams for Attrib. and other stories

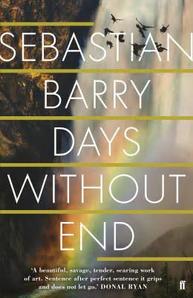

Days Without End by Sebastian Barry was published by Faber and Faber in 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed