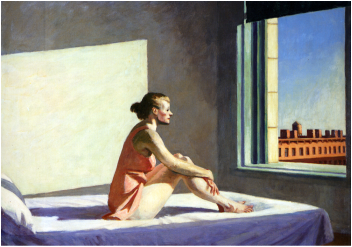

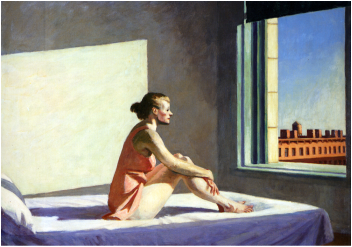

Edward Hopper: Morning Sun 1952

Edward Hopper: Morning Sun 1952

|

|

A week or so of hard frosts and record lows, fingers aching with the cold: and suddenly I’m a child again, winter Sundays resting my feet on the hot pipes below the pews and risking the delicious agony of a too-fast thaw. Eyes stream, nose runs, but the sun keeps shining, and the garden glitters as the icing on leaves and stems melts. I am stopped in my tracks by a hellebore, a deep purplish-pink. Charmed by its open face and finely etched veins, I stop for a photo. Later, at home, a bit of digging reminds me that many hellebores (from the Greek ‘elein’ to injure and ‘bora’ food) are poisonous. Aside from the misleading ‘Christmas rose’ – in fact this is member of the Ranunculaceae or buttercup family – the Helleborus niger boasts other nicknames, including ‘Christ’s herb’, ‘Clove-tongue’ and ‘Bear’s foot’. Although the entire plant is toxic, hellebore poisoning is rare, and it has a history of medicinal use for mental disorders as well as for the treatment of lice.  Too cold to stand for long but the glasshouses provide a welcome respite. There’s a buzz in the air there as the garden prepares for next month's Orchid Festival. My planned glimpse behind the scenes doesn’t happen – what I hope is only a temporary entanglement in red tape – but I happen upon a taste of what is to come in the Tropical House, where a single stem of Phaius tankervilliae, ‘Swamp lily’ or ‘Swamp orchid’, rises with the grace of a dancer from the damp earth. Like the hellebore, this orchid has an embarrassment of names, including ‘Veiled orchid’, ‘Nun’s orchid’ and ‘Nun’s cap’, from its curved, white-backed upper sepal and petals. It’s widespread in India, China & Japan and south-east Asia and is also found in Australia, although there it is regarded as an endangered species. The plant was brought from China to the UK towards the end of the eighteenth century by John Fothergill, plant collector and botanist who was also known as a Quaker and philanthropist, and a doctor with an expertise in the sore throat. It was named by Joseph Banks for Lady Emma Tankerville, whose name derived from Tancarville in Normandy, giving the species name its variant spellings. Somehow I miss the scent - what one commentary describes as ‘delightfully fragrant’ – so I promise myself a return visit.  Edward Hopper: Morning Sun 1952 Edward Hopper: Morning Sun 1952 A day or two later, I’m back in the Botanics. A small white downy feather floats in slow motion onto my palm. From the café, I watch a magpie strut across the flags outside. In fact I’m only half present, since I’m plugged into Raymond Carver reading ‘What we talk about when we talk about love’ – or rather to an introduction, which describes Carver arriving for this 1983 radio recording of his story, ‘bulky as a bear’, wearing a reindeer sweater and carrying a pile of student papers he’s in the process of marking. Carver’s characters, according to Herbert Gold's introduction, work in saw-mills, repair appliances, deliver mail. The problems they face are basic. They live in nondescript houses, cheap motels, sometimes dry-out centres. Now Carver’s reading has started, and I’m surprised by the lightness of his voice, and the brisk pace of his narrative. I’ve been reading Olivia Laing’s account of why writers drink, and Carver is included in her study. And this connection in turn transports me to London, specifically the British Library yesterday evening, for Olivia’s compelling and disturbing talk and readings from her forthcoming book ‘The Lonely City’, which she describes as a 'roving cultural history of urban loneliness'. Today, in pale sun, I’m haunted by one anecdote: after the death of Manhattan resident Henry Darger, his room was found to be packed with paints and paper, journals and writings and canvases and collages, product of ‘decade after decade after decade…’ living unregarded in the middle of the city.  Later in the week I down tools and take the train to Ipswich for the launch of a series of classes run by the English National Ballet Dance for Parkinson’s programme. I know pretty much what to expect: I’ve taken part in a training course and a taster session, and seen the video so I’m familiar with the format, the lengthy seated warm-up, a progression to standing and then to a marching/travelling sequence, some partner work and some whole group interaction, finishing with a passing-a-movement circle sequence. And I’ve met several of the group before. Still, I’m not really looking forward to it. I’ve been vaguely out of sorts for a week or two, alternately fighting off the January blues and succumbing to them, with a queasy stomach and lots of aches and pains. I’m also feeling a stubborn resistance to being a member of a group defined by disease. Once there, buffeted along the river and onto the waterfront by a vigorous wind, the warm welcome and the excitement of the providers boost my mood. Two of our sequences in the class, including a partner-mirroring exercise, are performed to the slow movement of Mozart’s piano concerto – the Elvira Madigan theme – quite magical. There’s time for tea and talk afterwards, and I make friends. As I leave Jerwood House, high-flying gulls form black silhouettes against a sky that seems rinsed clean, only a few smudges of bruised cloud and a clear half moon.  In Cambridge it’s still unarguably January, with flurries of hail and sleet and the odd snowflake interrupting the watery sunshine. There’s a song for the season in tango, of course – isn’t there always? – which equates the ‘white veil’ of winter with the ‘cold winds of desolation’ gusting through the lonely heart. As so often, the melancholy of the lyrics is enriched by the lovely chocolaty caress of Roberto Maida’s voice in this 1937 recording. Still, January’s almost out for another year. I’m all geared up for February and a new dawn (listen out for the birds towards the end!), hoping to learn about orchids in a Thursday lunchtime festival tour in Cambridge. I'll also be spreading my wings to take a look behind the scenes at Kew and to listen to Tom Hart Dyke talk about an orchid hunt which went disastrously wrong.

0 Comments

Actually, ‘casting’ is where it begins: friends arrive for Christmas Eve drinks several hours early, explaining that they have been casting, and have to get back to it. My brain tries angling and movie-making, both unlikely festive activities for this couple, until they clarify: they are making a mould, or rather a series of moulds. Recalibrated, brain and I attempt to understand the process, which goes: smear the object (details later) with the kind of quick-drying rubbery cement that dentists use for impressions of teeth. This becomes the mould. Then wrap or cover this in layers of plaster-of-Paris bandages, which make a kind of container or stand for the mould itself. I’m not sure how long these layers take to set, or what the object has been primed with to prevent layers of skin coming away with the cement – since the object in question is a breast. Ouch! The exciting thing about this part of the process is the degree of detail in the mould, goose bumps and all. And all of this is a prelude to the main job, which is slumping.  Slumping, I thought I knew, is what happens to brain and body when they’re just too relaxed for grace or comfort. It’s what I was always told off for in my early teens, when existential angst combined with burgeoning breasts to send me sliding hunched into whatever I could find to sit on and scowl from. It’s a state of mind – or emotion, perhaps more accurately – when despair hovers on dark wings at the edge of consciousness. Sometimes it’s associated with this time of year, when the post-Christmas blues combine with long nights and foul weather to dampen the toughest spirits. So in yoga this week I find myself working on the solar plexus, another of those terms which I thought I understood perfectly (as in an incapacitating blow to the tummy) but now find is also Manipura, the third chakra, my core self and source of power, self-esteem, willpower – and warmth. We are working to ‘brighten’ this chakra against the darks of winter, to wake ourselves into activity and optimism. I think, in one of those mind-wandering moments before I remember to drag myself back into the here and now, how the physical contours or sensations of the ‘slump’ are an apt metaphorical representation of financial slippage, personal or global.  A visit to the Garden reminds me that the natural world is already busy with its own brightening. I expected snowdrops, of course, but was surprised all over again by the delicious scents of the wintersweets, a kind of floral cough medicine, and the sudden injections of sweetness on the air from Daphne bholua and Viburnum bodnantense. I wander on from the spicy aromas of the scented garden and – how is it possible after haunting the place for more than eighteen months? – find yet another so far undiscovered corner, this a gravelled path running along the back of the winter garden. There are the yellows of flowering winter jasmine and mahonia of course, and hellebores, and then – here’s a real surprise – several clumps of ice-blue Iris unguicularis. Are these usually in flower so early in the year? What tugs at the heart, though, as I look back across this part of the garden are the stems – the fiery yellows and scarlets of Cornus sericea var. flaviramea and Cornus alba ‘Sibirica’, the orange firebursts of the pollarded willows and the Miss Havisham tangles of the ghost bramble. There are buds on the young cobnuts near the Station Road gate, and very sprightly rusty seedheads – are they seedheads? – on a tree I can’t identify over on the South Walk. Definitely no slumping here.  ‘Just google slumping and you’ll find it,’ my friend says. I discover that slump gives its name to a New England fruit pudding (also known as a ‘grunt’!) topped with ‘light, puffy steamed dumplings’ and to a geological form of ‘mass wasting’, a kind of landslip of loose rock, as well as to the ‘slump test’ which measures the workability of concrete. And yes, here is slumping: a technique of shaping glass in a kiln at a temperature just high enough for the glass to become flexible and slump into the mould, but not to collapse completely. It is then held at this temperature to allow it to ‘soak’ and then the kiln is cooled slowly to allow the glass to harden. Apparently the technique can be traced back to Roman times.  A post-Christmas visit brings photos of the results: both a close-up of the mould (including minute wrinkly bits and – yes – goose bumps) and of the finished item, looking rather like a clear sea shell. It’s beautiful, which leaves me thinking: perhaps there is an art to be learnt in allowing yourself to relax far enough into the mould of the moment to inhabit it entirely, without losing your shape altogether. Alternatively, a reminder of how little we know even when we think we know. Listening to Velvet Tango Radio recently, a relatively new discovery, I hear a vaguely familiar Pugliese instrumental called El Embrollo. Curious, I check the meaning. A translation gives me ‘imbroglio’ which I also have to look up, though I’m pretty sure it’s something along the lines of a brothel. So the definition is yet another surprise: an entanglement, a disagreement, a scandal, a confusion, a muddle. Which just goes to show… Velvet Tango Radio can be heard at http://radio.velvet-tango.net/ To listen to the 1952 recording of 'El Embrollo' (Pugliese's version) go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tP6Jf148OYg |

At HomeAs Writer in Residence, thoughts from the garden Archives

October 2020

Categories |