Last week (in Pepys mode again) to Kew, on the trail of orchids and their hunters. An unforgivingly dour and damp Thursday, the trek to the gardens (bus/train/tube/bus) knocking the edges off the romance of a plant hunt to foreign shores. We two, renewing an acquaintance from not far off half a century ago, were overawed by the size of the enterprise, both the Palm House itself and its contents at least three times taller/broader/and simply more than its Cambridge cousin. Our behind-the-scenes tour of the orchid nurseries (a similarly grand scale, though a welcome close focus) courtesy of volunteer Jenny provided ample advice on planting and growing though less on recent research-based expeditions. As for the orchid displays themselves: well, some exquisite specimens, a breath-taking extravaganza of colour and form and a really impressive show, although I left with a feeling akin to having eaten too much chocolate.

A new species? Photo: Andre Schuiteman

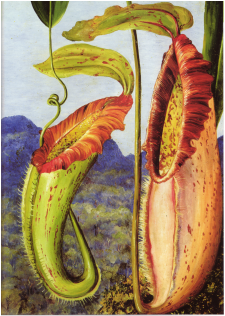

A new species? Photo: Andre Schuiteman  Marianne North: Nepenthes northiana

Marianne North: Nepenthes northiana

The Cabaret of Plants by Richard Mabey due to be published in October 2015

Etta James sings 'At Last' (1961)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed