|

|

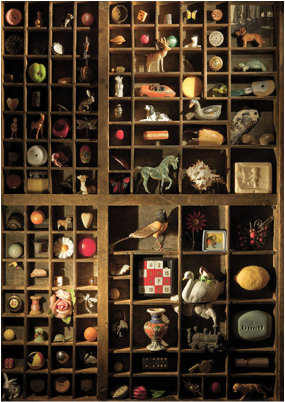

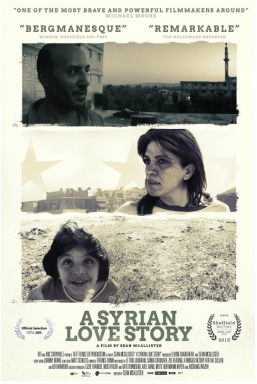

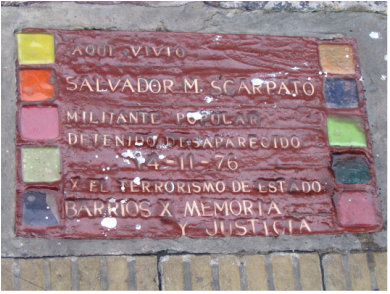

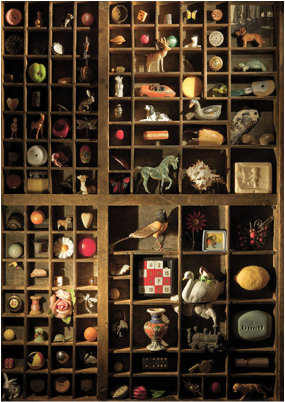

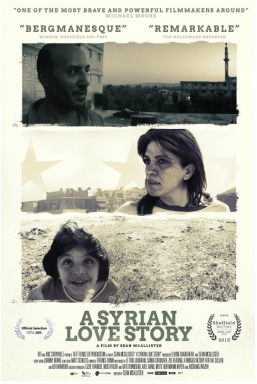

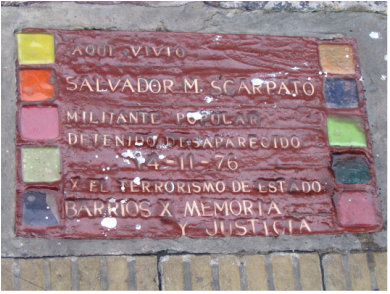

The day begins with a post from Mick, reporting on Day Six of his group’s visit to Buenos Aires and Day Three of their ‘training’: a tough regime which has left Mick’s shoulders ‘like raw meat’. One sentence really strikes a chord with me: ‘only my tango friends know that when you come on something like this you start again from the beginning.’ At once I’m back in Argentina, if only for a few minutes. I don’t remember experiencing sore shoulders but my memory produces its own lows – the days when my arm swelled to a balloon after a mosquito bite and I took to my bed convinced I had dengue fever, or the night I paid several hundred pesos for the services of a charming taxi dancer in Club Gricel and then lost my nerve so completely that I couldn’t dance at all – as well as plenty of highs, which blur now into a kind of composite glow, jacarandas in bloom, street life sounds from the balcony, dancing to a perfect Pugliese tanda in the early hours…  If I had known then that one of these moments would be the happiest moment of my life, would this have changed things? What would I have done differently? The question is raised at the beginning of Grant Gee’s extraordinary film ‘Innocence of Memories’ which I saw at the Arts Picturehouse yesterday morning. Described by one reviewer as ‘a collage of textual fragments, painterly visuals and mysterious voiceovers’, the film is based on the 2008 novel The Museum of Innocence by Nobel-prize winning author Orhan Pamuk, and includes Pamuk’s own voice in interviews and readings. The camera takes us through the streets of Istanbul and inside the real-life ‘Museum of Innocence’ which Pamuk constructed in parallel with the novel, to house the objects ‘collected’ by the central character Kemal as a record of his doomed love affair. The film is many-layered, intriguing, beguiling. I found it totally absorbing and loved the way it played with our notions of time – a spiral rather than a line, the film suggests – and with fiction, one memory joining another to make a story: ‘there is always a story’. How to tell that story is a question which taxes every writer. Overlapping narratives here are interrupted by the voices of ‘real’ individuals in present-day Istanbul – a taxi driver, a rag collector, a ferry-boat worker – another reminder that ‘real life’ has its place in fiction too. Strangely, although Kemal’s story is one of repeated loss, his verdict is, ‘Let everyone know, I lived a very happy life.’  I’ve never been to Istanbul but I’m familiar with the tug of the far-away, which features in Brian Friel’s ‘Philadelphia Here I Come’ currently running at the Corpus Playroom. The protagonist Gar is desperate to escape the confines of small-town Ireland and in particular a dead-end job working for his father in his shop. The action takes place on the eve of Gar’s departure to a new life in America. Through the clever device of two versions of the character, his public self and ‘Gar (private)’ we experience his fantasies about the opportunities which his new life will bring, as well as the frustrations of living at home, especially the total lack of any meaningful communication with his father. The inane predictability of their non-conversations, though often very funny, reminded me of the sometimes infuriating lack of real connection in my own early family relationships. On several occasions Gar tries to break through the banality, reminding his father of a fishing trip they went on when he was young. The details – the blue boat, and his dad wrapping him up in his coat – make up what is for Gar a precious memory of the love between father and son, now long lost. Only in the last moments of the play do we discover, in Gar’s absence, that his father has his own tender memory of a time before the relationship foundered: the boy Gar in a sailor suit, refusing to go to school and insisting he would stay home instead and work for his dad.  Later I attended a special showing of a very different exploration of love, family and memory. Filmed over a five-year-period by independent British film-maker Sean McAllister, ‘A Syrian Love Story’ tells the story of Raghda and Amer who first met in a Syrian prison 15 years ago. The film picks up their story in 2009, when Raghda is a political prisoner and Amer is caring for their four sons alone, and ends with their eventual political freedom in the West in 2015. Although on paper this might look like a happy ending – all six are safe, have escaped from the multiple dangers of life in Syria and have a future – McAllister documents faithfully the difficulties and torments of their journey. Almost a seventh family member (‘I don’t go for objectivity,’ the director said during the Q&A session afterwards. ‘I’m less a fly on the wall, more a fly in the soup.’) McAllister is with the family through imprisonment (he spent five days inside a Syrian prison himself), political turmoil and escalating violence, the disintegration of Raghda and Amer’s relationship, the family’s flight to Lebanon, and Raghda’s attempted suicide. Warm but never sentimental, the film’s unflinching gaze makes it appropriately uncomfortable to watch. How could it be otherwise? Moving house is apparently the single most stressful factor in our lives, McAllister reminded us in the closing minutes of the discussion; Raghda and Amer and their family moved house 16 times during filming.  ‘A Syrian Love Story’ backtracks at the end, collecting and replaying key moments from those five years. Looking back, it seems, is an integral part of our attempt to make sense of where we are now, what we have become, and where we are going. My good friend and artist Di Clay and I are still knee-deep in an exploration of our own memories, which we hope somehow to map. We are collecting objects – though not quite with the obsessiveness behind Kemal’s collection of 4,213 cigarette butts from his lover – and assembling writings and photos. Sometimes we plan an exhibition though we have – so far – stopped short of a whole museum! Every now and then we meet to grapple, inconclusively as yet, with ways of depicting our overlapping journeys to a wider audience. This morning, blue skies and wintry sun transport me back to magical mornings in early spring when I was young – was this the moment when I was happiest? Or that one? – and then to sunlight on the cobbles of San Telmo, where the recovery of memories of the past, guilty and innocent, has been a key element in the search for justice and truth, and where the names of some of the disappeared are now, literally, set in stone. An exhibition The Museum of Innocence, a collaboration with author Orhan Pamuk to accompany novel and film, is at Somerset House until 3rd April.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

At HomeAs Writer in Residence, thoughts from the garden Archives

October 2020

Categories |