'September': Gerhard Richter 2005 MoMA. New York

'September': Gerhard Richter 2005 MoMA. New York

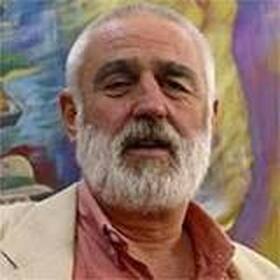

Issa Perillo Founder & Executive Director of Go! Tango P.D.

Issa Perillo Founder & Executive Director of Go! Tango P.D. Cassie stood out in our tango world in so many ways: never a comfortable fit, she tended to ride roughshod over tango’s codes of behaviour and was often hurt by her lack of acceptance. But she will be remembered for her determination and courage, her idiosyncrasies, her sense of humour and her generous spirit. I know that she found tango helpful for her experience of Parkinson’s and I’m sorry that she won’t be around when The Tango Effect is published next year. The book has attracted a bit of attention online recently, not just in the UK – an invitation to speak at the Lichfield Literature Festival in March, for example – but also in the US. One approach came from Ninah Beliavsky, Professor of Linguistics at St John’s University, New York who took my story with her to Buenos Aires where she addressed a conference on unspoken communication in Argentine tango. The second, most recently, was from Issa Perillo, a dancer diagnosed with early onset Parkinson’s in 2011. With movement specialist Gloria Araya, Issa now teaches regular adapted tango classes for people with Parkinson’s tango in Chicago (check out her website here). We spoke on Skype a couple of days ago, comparing our experiences and I’m very much hoping we will stay in touch. Issa wanted to know if I was likely to be in Chicago any time soon. While I tied myself in knots with my very English evasions, she was refreshingly open about my gastric problems and not afraid to call a bowel a bowel, leaving me feeling optimistic: that what has begun to seem like a life sentence, an early end to travel opportunities, might actually be resolvable.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed