Leaving the motorway we stop twice, searching with scant success for evidence of C’s ancestors and move on, skirting the southern edge of the city, inching crabwise towards our destination. Memory flaps between recognition and strangeness like a sheet on a line - that curve in the road displaced by new build, the expected turning further than I remember. C talks, picking over the bones of an old love. I am half listening, half present, the rest of me taut with apprehension, anticipation. Red brick, weathered to crumbling, glows in the afternoon sun. Take care, I want to say, this is a dangerous bend but there's no need. And then there is the village sign, the dip in the road, the farm on the left.

We park round the corner at the lane end and walk up to the house. I feel the need to defend it from C’s unspoken criticism although it had no part in my growing up and I had no love for its bricks and mortar, not even for the garden, when I came to it as an adult. A moment is all it needs. We turn back and head between high hedges up the lane to the church. I wonder how many hundreds of times I‘ve walked this stretch of road, escaping the confines of what had become the family home, lighting the first cigarette once out of sight At a gap in the hedge we stop and look back at the house. What was a small acer has become a crimson fire. I point out the lone oak in the field. I used to look out at the tree from my bedroom window, I say, remembering as I speak that my room had no view over the back garden.

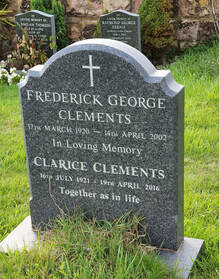

It’s a stiff pull up the path to the small church which squats square and defiant on its hilltop, the entrance opposite the vast split trunk of a yew. I wonder which has been here longer, church or tree? All Saints dates back at least to the eleventh century and what survives is now a listed building. I think of other feet making the same short climb over the centuries and of our own traffic through the years: weddings and funerals, Christmas and New Year celebrations and the day-to-day routines of a church-going family. My head fills with photographs of our own special occasions, many of those pictured long gone. Today, though, the church is not my business; I walk past and follow the trodden earth along the side of the graveyard almost to the end where the land falls away into the valley: the best view in the county, I’ve always said, if only they could see it.

She would have appreciated this afternoon, too: the warmth of the sun, the murmur of farm machinery, the gently rolling landscape softened by trees, the first hint of the autumn colours she prized. No fan of big open spaces or the wild, she was frightened of water. Hers was a quiet life. She had no real interest in music, was apt to dismiss my dad’s loud-volume listening as a ‘din’ although she liked Gilbert & Sullvan - as long as it was delivered by the D’Oyly Carte Company. Her ultimate punishment, one stage further than the quick slap on the upper arm or the back of a thigh, was the silent treatment. She could keep it up for days. And yet, and yet… as I push the trowel deeper, worrying at the impacted roots, I see I have barely broken the surface of who she was. I remember her determination, returning to school in her fifties for ‘O’ and ‘A’ levels, her jam-making and silver-smithing, the sense of humour she shared with a few close friends, the understated elegance she worked so hard to achieve. I don’t think she ever made her peace with her northern origins but I promise myself, on my next visit, to plant the low-growing rose ‘Lancashire’ and imagine the roots finding their way into her bones.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed