I’ve been thinking about the term ‘grounded’, the way it’s migrated from the negative connotation of being prevented from flying or run aground, high and dry to the now more familiar sense of being mentally or emotionally stable: to have your feet on the ground; to be in the here-and-now. There are apparently techniques to help manage intense anxiety, and responses to feeling knocked for six by life’s vicissitudes which involve building, or rebuilding, a relationship with the earth. Whilst emotionally I find myself on fairly secure ground just now, the literal sense of trusting the earth beneath my feet is lost to me. I don’t want to make too much of this. Remembering my mum’s propensity for falls in her last year or two, her face more often than not a spectacular array of livid colours, or watching the elderly and infirm clutching the rails of the Jesus Green footbridge as they inch their way across, I recognise that by comparison I’m a model of equilibrium. It’s provisional, though. ‘Postural instability’, one of those cumbersome terms that have attached themselves to Parkinson’s – as if the clumsiness of the condition weren’t annoyance enough! – is a fact of life now. I’m careful not to look up or turn quickly in the shower. I watch out for anything which might trip me up when I’m out and about. Increasingly, I’m prone to falling over my own feet. Cycling must be timed to coincide with periods when the medication is likely to make me relatively safe; it doesn’t always work.

My hold on life feels especially precarious at the moment since I’ve set myself in motion, pulling up my Cumbrian roots and then, as if that weren’t enough of a destabilizer, my Cambridge roots too. Yes I know I’m only moving round the corner but the time factor has confounded me rather. I’m not sure how long it is since I packed my first box of books but I’ve become so used to living surrounded by the things that somehow this state of impermanence has become the new permanent. It feels as if I’m on hold, caught up in one of those interminable telephone conversations interrupted at intervals with the hollow assurance that ‘your call is important to us’, unable to settle to anything productive, forever marking time. When I do eventually receive the keys to the flat, most of a year will have gone by.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, I’ve been drawn to reflect on what endures. I’ve recently discovered Sebastian Barry. How have I missed him for so long?! This from the sequence in his latest novel which gives it its title, Days Without End:

Time was not something then that we thought of as an item that possessed an ending, but something that would go on forever… The heart rising, and the soul singing. Fully alive in life and content as the house-martins under the eaves of the house.

I trawl my memories for such moments of joy. Grief lasts too, I suppose, the awareness of loss persisting like a drip of water on stone, always eroding, never done. Hurts can linger too although may be susceptible to the desire to forgive, or be forgiven. What we try to have and hold for the safety and security of ourselves and our children, though, these are the things which most elude or defeat us. A house can soak up all our resources, literal and emotional, and be destroyed in an instant. Health? A given, until it’s taken away. Careers we build our lives around are lost overnight. Trees planted, lawns laid, investments made, plans drawn up, money saved, partners and friends claimed – all ephemeral, the more we invest emotionally in these things the more vulnerable we make ourselves to despair. Hope can sustain us until it disappears without warning: ‘I have of late,’ Hamlet says, ‘– but wherefore I know not, – lost all my mirth...’ Life itself can be ripped from us just when we feel it will last for ever. So where should we lodge our hearts? What game is worth the candle?

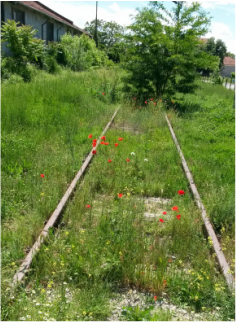

The process of packing has rendered the past very present for me. My dad was an inveterate record-keeper, taking photographs of every family occasion and, strangely it seemed at the time, every new house or car, as if these material acquisitions were markers of our purchase on or progress through the world. He filled album after album of such snaps and produced laboriously typed lists – antique furniture bought, classical music tapes recorded. In his last years, the digital revolution only took him as far as transferring the lists to his computer – he still printed out the results. Our piano, the biggest challenge in my many moves, was his piano, bought, so the story goes, by his dad for half a crown from a man they saw pushing it on a bogie up the road in Aspull. It bears the scars of its many journeys and is irrevocably out of tune but I have to find a way for it to accompany me to my fifth-floor flat. I have been pretty ruthless with other leavings: a clock presented to him on his retirement has gone to my friend’s brother, one of his watches to my son, another to an old boyfriend. But other relics still surface, in particular the trappings of a railway life. When he died, we rashly got rid of the thousands of slides, though the memory of stifling Sunday evening slide shows still lingers, one locomotive after another appearing on the screen as we yawned and fidgeted our way through the sequence, lulled almost to unconsciousness by the hum of the projector and the sound of his voice. On the shelf above my desk there is a tray with a teapot and hot water jug, silver-plated and much tarnished, from the old railway restaurant cars which my dad brought home one day from a sale. I’ll never use them, but I can’t bear to throw them away.

The first anniversary of our mother’s death will be just after Easter. My dad died almost 15 years ago, the day after my birthday, which this year falls on Maundy Thursday. And then Good Friday and what has become a family tradition of queuing for the annual Ante-Communion and Veneration of the Cross in King’s College Chapel. On Saturday, also at King’s, tenor Mark Padmore leads the Britten Sinfonia in Bach’s St John Passion. Writing in Saturday’s Guardian, Padmore contrasts what he describes as our ‘age of anxiety for preserving things’ with Bach’s world, where 11 of his 20 children died before he did and all his four performances of the St John Passion had to accommodate changes according to availability of instruments or players, or changes in theological fashion.

Last week I saw ‘The Olive Tree’, an absorbing exploration of family and friendship, what we need to keep and what we can afford to let go. The thousand-year-old tree of the title has been sold. The film traces the effects of the loss on the grandfather and its repercussions on the rest of the family. Granddaughter Alma’s hare-brained scheme to recover the tree is never going to succeed – or perhaps the way the story unfolds encourages us to reconsider notions of success and failure. It’s told with a lightness of touch and lots of humour, and a reminder that uprooting is not necessarily the end of growth.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed